Law

Social Enterprises Have a Triple Bottom Line

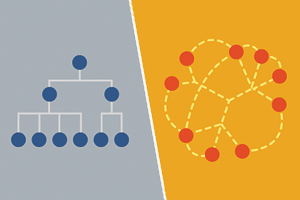

An old stereotype separates nonprofits from for-profits in this way: nonprofits do good and for-profits make money. Legal structures demand that heads of corporations serve a single goal for their shareholders: maximizing profit. You could get sued if you let other priorities — the environment or a public mission — sully that transaction in such a way that it decreased profit.

At the same time, many nonprofits have struggled to balance meeting real community needs with a constant fund-raising cycle that leaves their longevity in the hands of sometimes fickle donors and foundations.

Over the past few decades, social enterprise has cut a path somewhere in between.

As Robert Tomasko, director of SIS’s social enterprise program explained, “Social enterprise makes use of private sector techniques, but for public purposes.” These businesses turn a profit, but at the same time serve a social mission. Some call it a triple bottom line: people, planet, and profit.

For law students about to enter the job market, new and developing state legislation creating new social enterprise business formations — L3C’s (low-profit, limited liability companies) and benefit corporations — makes this is a prime time to prepare for an emerging legal field that combines associations, corporate, tax, and nonprofit law. As part of an effort to understand the legal implications of this emerging sector, Washington College of Law (WCL) students founded the Social Enterprise Legal Society.

A Grain of Inspiration from TED and WCL

Second year law student Karina Sigar is no stranger to social enterprise. Hailing from Indonesia, she was one of the cofounders of TEDxJakarta, a community outshoot of the popular idea-driven TED conferences. In helping organize talks for TEDxJakarta, Sigar met social entrepreneurs using business methods to bring electricity to rural villages and fight deforestation — ventures that reinvested profits to help more people and make a positive impact on the planet.

“TED sort of allows me to encounter these people who I wouldn’t meet otherwise,” Sigar said.

Since the field of social enterprise itself is so new, and laws to define its scope are still being written, it’s not the sort of standard subject that appears in a law school course catalogue. Yet in Walter Effross’s business associations class, Sigar found a faculty member with an interest in social enterprise, who integrates the subject in order to show the breadth of associations law — and it’s applicability to subjects that matter deeply to WCL students.

Said Effross, “The whole emerging concept of social enterprise really marries the social justice interests of the students and the faculty of the law school as an organization with more traditional bottom-line oriented issues.” He hoped to give students a new perspective on standard business associations but also a foothold in an emerging sector. Integrating social enterprise into his associations and, this semester, corporate law class “brings up good legal issues that are yet to be resolved, but also lots of good opportunities for jobs.”

In his business associations class, Effross suggested to his students that a social enterprise legal society would be a very useful organization. A number of students, including Kyle Vitek, Kevin Frisch, and Sigar, agreed and founded the group, which Effross now advises.

Thus far, plans for the society include:

- frequent, small-scale events and weekly meetings where students share research about the field

- interviewing social entrepreneurs

- planning content for their blog

- working to understand the legal realities social enterprises are beginning to face

Said Sigar, “We’re in it, not just because we want another line to put on our résumés, but because we love the topic and we want to talk about it on a regular basis.

The Social Enterprise Legal Society is welcoming students from across campus with an interest in social enterprise law, and SIS’s Tomasko noted that master’s students in the social enterprise program are eager to collaborate with the law school. Certainly, the weekly meetings will give students specialized knowledge, and Tomasko acknowledged that people starting social ventures will need advisors with legal and financial knowledge. “But the biggest contribution people with legal expertise can make to social enterprise is not helping file incorporations and tax returns, but helping create new legal and financial structures that will drive the future growth of social enterprise.”

To learn the early law of social enterprise is to prepare to write its future.